- The practical fix is verification, persist definitions and time boundaries, validate scope, and check alignment before decisions.

- General purpose models should be used for speed, however output should be treated as directional and not the final truth.

- The biggest failures are silent : queries run, charts look right, and the answer can shift.

- Most of the analysis drift happens in a few places, time windows, joins and grain, scope and denominators, and follow-up context.

- There are two main driving forces : Run-to-run interpretation variance and business terms being rebuilt from context.

Introduction

A few years ago, if you asked me whether general purpose language models like ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini could meaningfully replace large parts of day to day data analysis, I would have said yes without much hesitation.

The progress was obvious. These models were getting better at understanding business questions expressed in plain language, translating them into queries, and presenting results in a way that felt usable to non technical teams.

Nothing crashed. Queries ran. Charts rendered. The answers looked reasonable and often aligned with expectations. The problems only surfaced later, when someone slowed down and checked the work more carefully. What you would find is – results that look correct, but often aren't.

The risk was not that these models made mistakes. The risk was that the mistakes were easy to miss, difficult to reproduce, and results were convincing enough to shape decisions before anyone realized something was off.

What follows is a reflection of what becomes visible once general purpose language models move beyond demos and into sustained, real world use as analytical tools.

Why the pitch works so well

I understand why the pitch for using AI for data analysis lands. (After all, I am betting my career on it).

- Ask a question in plain language

- Get an answer in seconds

- Skip the data team ticket queue

- Avoid the SQL bottleneck

And the technology has earned some of that excitement. Modern reasoning models can navigate complex schemas, write sophisticated queries, join data across systems, and produce charts and narratives that resemble the work of experienced analysts. In controlled settings, the results can be genuinely impressive.

The gap shows up once you leave the sandbox. In production, the hardest problems are not crashes or syntax errors.

They are the moments when a query runs successfully, the output looks right, and only later you realize it answered a slightly different question than the one you meant to ask.

The consistency issue you probably recognize

After testing across leading models including Claude, GPT, Gemini, DeepSeek, and maybe a dozen others, a pattern shows up with surprising consistency. Confabulation and inconsistency are not rare glitches. They are natural outcomes of how these systems operate. If you have spent enough time with them, this probably feels familiar.

Ask the same question multiple times and you may receive different interpretations. That is not the model breaking. It is the model sampling from a range of plausible responses.

In creative tasks, that variability can be a benefit. In data analysis, it becomes something you have to design around.

When a two percent swing in calculation can have cascading impact to fully alter hiring plans or revenue forecasts, probabilistic interpretation becomes a risk factor. The combination of ambiguous language, statistical generation, and the absence of verification is where problems tend to appear.

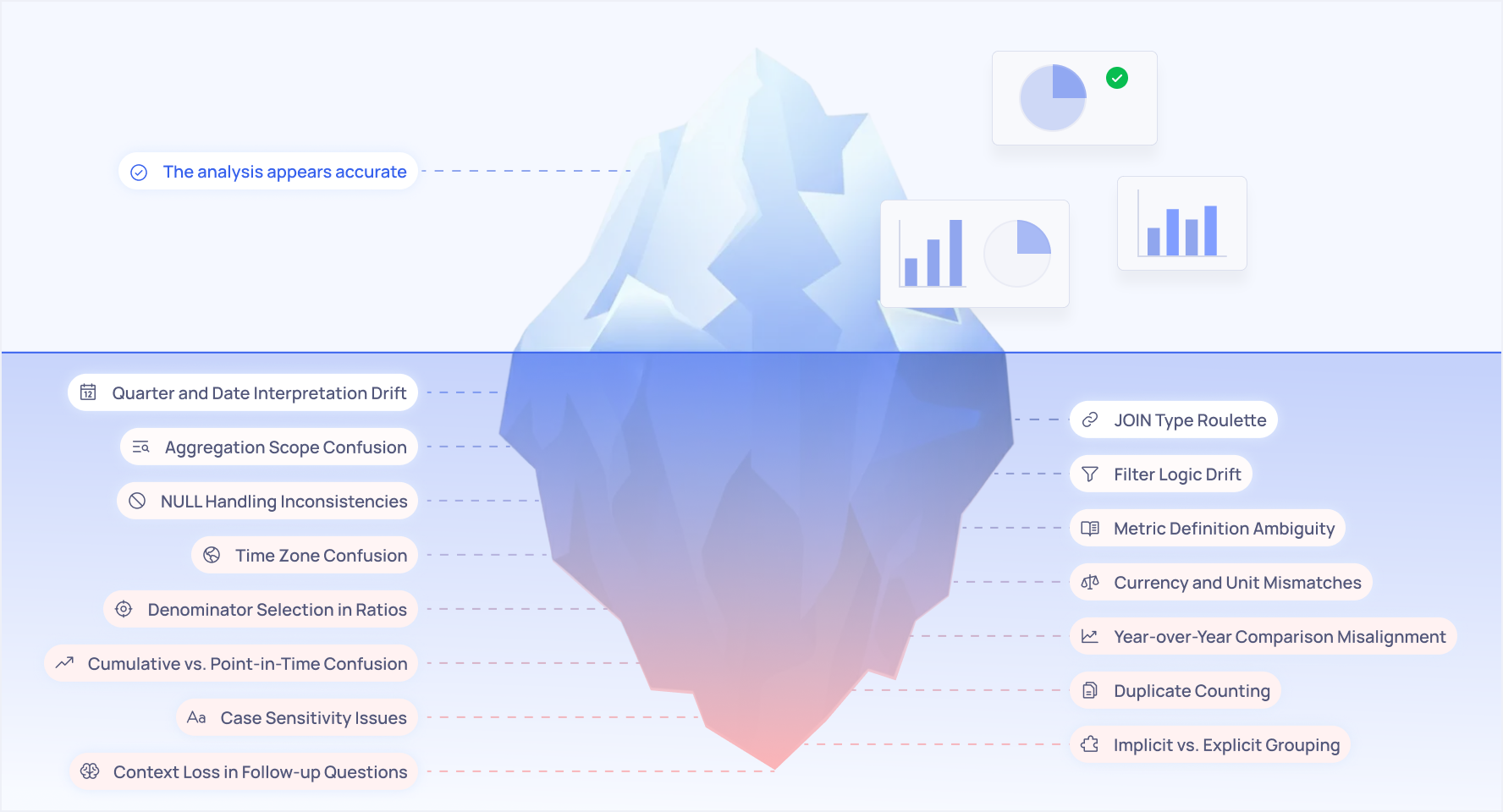

15 silent ways analysis drifts when you rely on general-purpose models

The 15 Silent Killers of AI Data Analysis

Through extensive testing and real-world deployment, we've catalogued the most common failure modes. These aren't edge cases - they're patterns we see repeatedly across different models, different schemas, and different business contexts.

1. Quarter and Date Interpretation Drift

When a user asks about "Q3 performance," does that mean calendar Q3 or fiscal Q3? Does "last quarter" mean the most recently completed quarter, or the previous one relative to that? LLMs will interpret this differently based on subtle contextual cues - or sometimes, seemingly at random.

Real impact: A retail company's "quarterly growth" metric varied by up to 40% depending on which interpretation the model chose.

2. JOIN Type Roulette

LEFT JOIN or INNER JOIN? This seemingly technical decision has massive implications for your numbers. A LEFT JOIN preserves all records from one table even without matches; an INNER JOIN only keeps matched records. Ask the same question on different days, and the model might choose differently each time.

Real impact: A SaaS company's "customers with support tickets" count fluctuated by 23% based on JOIN selection.

3. Aggregation Scope Confusion

"Total revenue by region" seems straightforward. But should we sum all transactions, or sum only completed ones? Include refunds or exclude them? The model makes assumptions, and those assumptions aren't always consistent. Without an explicit, reusable metric definition, each query becomes a fresh guess at what “total” means.

4. Filter Logic Drift

"Show me high-value customers" requires defining "high-value." The model might use top 10%, top 20%, or an absolute threshold - and that choice might change between queries. Even within a single conversation, the threshold can silently change if the model decides that “enterprise” or “strategic” implies a different cutoff.

5. NULL Handling Inconsistencies

How should NULL values be treated in calculations? Ignored? Treated as zero? Excluded from counts? Different interpretations yield different results, and LLMs don't always handle this consistently. This is especially dangerous for ratios and averages, where “include vs. exclude NULLs” can flip a trend line.

6. Metric Definition Ambiguity

"Churn rate" means different things to different businesses. Monthly? Annual? Based on revenue or customer count? Logo churn or net revenue retention? The model guesses based on context, and context is often insufficient. Unless the definition is explicitly stored and reused, each answer may encode a slightly different version of “churn.”

7. Time Zone Confusion

When does "today" end? For a global business, a sale at 11 PM PST might be "today" or "tomorrow" depending on how time zones are handled. Models rarely ask for clarification. If warehouses, billing, and product usage sit in different regions, this can shift revenue and activity between days, weeks, or even quarters.

8. Currency and Unit Mismatches

Multi-currency data is a minefield. Did the model convert to a common currency? Use historical rates or current rates? Mix dollars and euros without conversion? These errors produce results that look valid but mean nothing.

9. Denominator Selection in Ratios

"Conversion rate" requires a numerator and denominator. Which population is the denominator? All visitors? Unique visitors? Visitors who saw the product page? Small changes in denominator selection cause large swings in the final number.

10. Year-over-Year Comparison Misalignment

Comparing this February to last February sounds simple until you remember that last year was a leap year. Or that Easter fell in March last year but April this year. Business context matters, and models often miss it. Seasonality, campaign timing, and holidays all matter, but the model typically sees only timestamps, not your commercial calendar.

11. Cumulative vs. Point-in-Time Confusion

"How many active users do we have?" Could mean active users right now (point-in-time) or users who have been active this month (cumulative). The difference can be 10x. Without a standard, persisted definition of “active,” the same phrase can yield wildly different populations.

12. Duplicate Counting

A customer who bought three products - should they count once or three times in "customer count"? The answer depends on the question's intent, which models frequently misread. If the underlying tables are not fully de‑duplicated, LLMs will happily double‑count and still produce perfectly valid SQL.

13. Case Sensitivity Issues

In some databases, "ACME Corp" and "acme corp" are different customers. In others, they're the same. Models don't always know which world they're in, leading to over or under-counting. Even within the same stack, different tools (warehouse, CRM, billing) may handle case differently.

14. Hidden Whitespace and String Matching Issues

Multi-select picklists, user-input fields, and migrated data often contain trailing or leading whitespace that's invisible to both users and LLMs. A user asks for "customers in the Enterprise segment," and the LLM generates WHERE segment = 'Enterprise'. But the actual database values are 'Enterprise ' (with trailing space) or ' Enterprise' (with leading space) due to data entry inconsistencies. The query returns zero records, and both the user and the system are confused, the data exists, but the exact string match silently fails.

15. Context Loss in Follow-up Questions

Perhaps the most insidious: the model loses track of context across a conversation. You ask about "enterprise customers," then ask a follow-up about "their average deal size," and the model forgets the "enterprise" filter. Your answer includes all customers, not just enterprise. To the user, it feels like a continuation; to the model, it is often a fresh question with only partial remembered constraints.

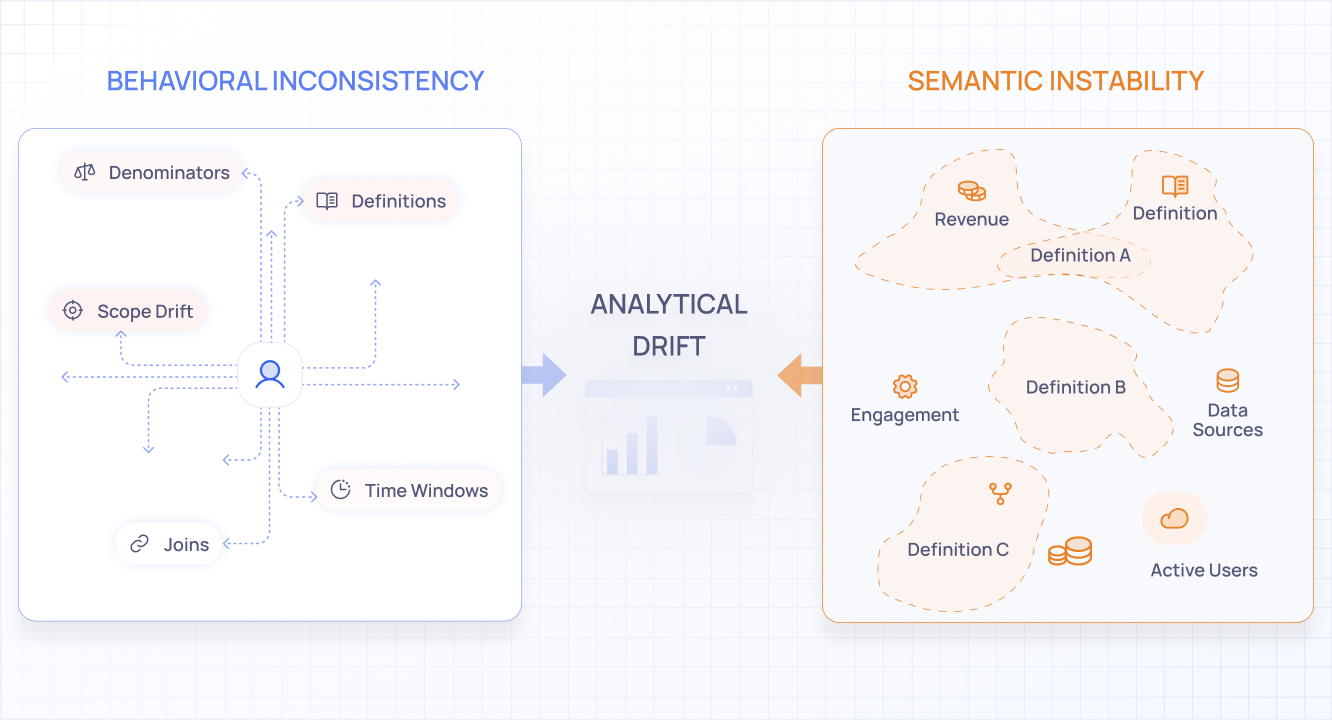

The underlying pattern behind most drift

If you study these 15 failure modes carefully, a pattern emerges. They all stem from two fundamental problems, and they reinforce each other.

Behavioral inconsistency shows up when the same question produces slightly different interpretations across runs.

- A model may interpret "last quarter" relative to today in one response and relative to a prior comparison window in another

- It may choose a different join strategy, grouping level, or filter threshold even when nothing has changed

Each individual choice is reasonable in isolation, but the lack of repeatability makes the output difficult to rely on.

Semantic instability appears when business concepts are reconstructed each time they are mentioned.

- Terms like churn, active user, or enterprise customer do not carry a fixed meaning inside a general purpose language model

- The model rebuilds meaning from surrounding context, which is often incomplete

As a result, the same metric label can quietly refer to different populations or calculations across analyses.

At the core of both issues is how language models operate. They generate responses probabilistically, selecting from a range of likely interpretations rather than executing a single, fixed logical path. That is what makes them broadly useful. It also means an output can feel coherent while drifting away from the precise question being asked.

The models are brilliant at generating plausible responses, but plausibility and accuracy are not the same thing.

Why prompts and fine-tuning do not solve this on their own

The first wave of fixes tends to focus on tightening the model itself. Some of them help, but none of them really remove the instability.

- More detailed prompts can clarify intent upfront, but real analysis rarely stays fixed

- Fine tuning and templates improve consistency for known patterns, but trade flexibility for control

- Self checking adds review, but rarely challenges the assumptions that shaped the original answer

What all of these have in common is the unit of improvement. They assume the model can be pushed into acting like a reliable analytical system on its own.

The recurring failures point elsewhere.

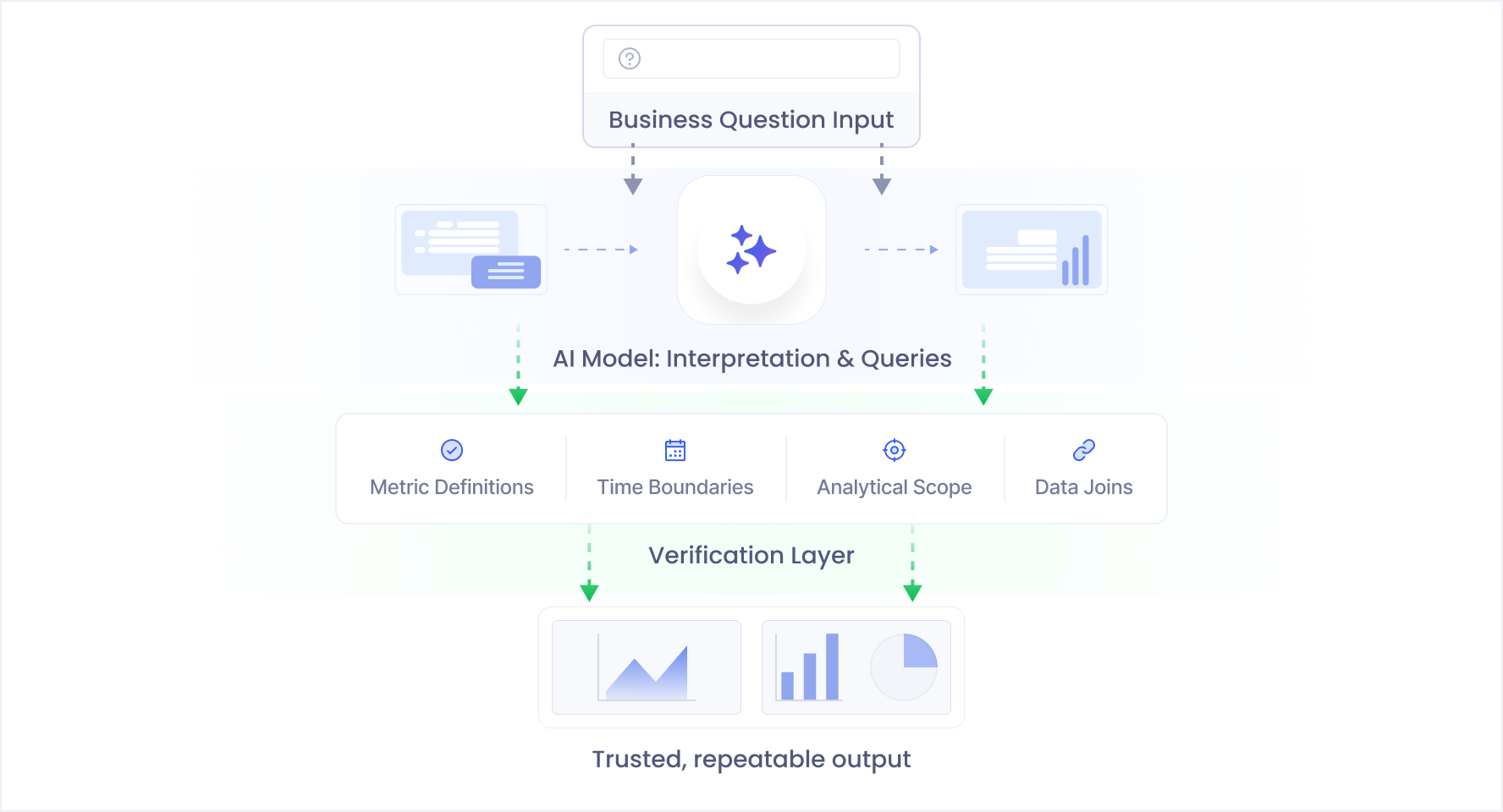

The missing component is verification.

A verification-first direction, and a reason for optimism

What makes me optimistic is that none of this says AI has no place in analysis. The strengths of general purpose language models are real. They are fast, flexible, and unusually good at helping people work through messy questions that do not fit neatly into predefined dashboards.

The trouble starts when those strengths are treated as sufficient on their own.

In mature analytical systems, reliability usually comes from design choices that assume mistakes will happen.

- Inputs are constrained

- Assumptions are made explicit

- Outputs are checked against expectations and contracts

A verification first approach brings that same discipline to AI powered analytics.

Instead of asking a model to be both creative and correct, the system separates responsibilities.

- Models propose interpretations and analytical plans

- Independent layers verify alignment with definitions, time boundaries, and data constraints

In this framing, language models become powerful collaborators rather than final authorities. They accelerate exploration while verification supports consistency. The goal is not slower analysis. It is analysis that can move quickly without quietly drifting away from intent.

Verification needs to operate throughout the process.

- Interpretations need grounding in durable definitions

- Queries need validation against the question being asked

- Results need checks for temporal, semantic, and structural alignment before they are treated as decisions

A Different Approach Is Needed

If hallucination and inconsistency are inherent to how LLMs work, then the solution isn't to make a single model more accurate. It's to build systems that verify accuracy at every step.

Think about how traditional software handles unreliable components: redundancy, validation, cross-checking. Critical systems don't trust any single component absolutely - they verify.

The same principle applies to AI-powered analytics. Every interpretation needs verification. Every query needs validation. Every result needs cross-checking against intent. You need a way to ask, at each step: “Is this what we meant, according to our own definitions, data contracts, and business rules?”

But this verification can't be an afterthought or a final check. It needs to be woven into the fabric of the analysis process itself. Distributed throughout every step. Handled by specialized systems that understand what "correct" means from multiple angles - structural validity, semantic accuracy, temporal consistency, behavioral alignment, and compliance with business rules.

This is the direction we've been building toward. In our next post, we'll explore why traditional approaches to improving LLM accuracy fall short, and begin to outline what a real verification architecture looks like.

Because the question isn't whether AI data analysis will become essential - it already is. The question is whether we can make it trustworthy.

This is Part 1 of a 4 part series on LLM verification in AI powered data analysis.

Part 2. Why Guardrails, Prompts, and Fine Tuning Won't Save You →

About Petavue

Petavue is building the verification layer for data analysis using general purpose language models. The idea comes straight from the failure modes in this piece. The models are often helpful in proposing an analysis, but trust comes from repeatability.

Petavue helps teams make that repeatability practical by:

- grounding questions in shared metric definitions and time boundaries

- validating query structure and scope against the approved plan

- producing a clear, reviewable trail of assumptions and checks, so the same question yields the same meaning over time

If you are exploring how to use AI for data analysis without losing repeatability, we will walk you through how Petavue works with your definitions, time boundaries, and workflows.

![[Data Story] Investigating San Francisco’s Feelers: Correlation Between Disorder, Crime and Administrative Strain](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/675e93d0c15c6d2e3ed70f0e/6942c4ce34e004dd8e77a3da_File.png)